As experienced health professional students seek additional education, in-service training, and continued professional development opportunities to further their careers, some types of gender discrimination may shape their career paths, which can potentially lead to the underrepresentation of females or males in certain health worker cadres and/or specialties.

Caregiver responsibilies discrimination

Institutional policies and practices may prevent or limit health workers from accessing training and continued professional development opportunities, by failing to consider their family responsibilities and the extra time that students with children may need for breastfeeding or child care, or for other domestic and caregiving tasks. Female health workers may also have potential safety concerns related to extracurricular activities that take place outside of regular working hours, when secure and affordable transport may not be available.

“We have different roles. If we go home the two of us, I make sure the baby is well fed, then asleep, husband taken care of…that affects my concentration…while [when] he goes home he expects food [to] be ready.” —Kenyan health professional student (Newman et al. 2011)

Attitudes discourage female medical residents from becoming pregnant (US: Finch 2003)

“I had two supervisors, one of whom was very angry with me because this was my second pregnancy, and he felt that I was putting the program at risk by becoming pregnant again.” —Canadian family medicine resident (Walsh et al. 2005)

Sexual harassment

During medical training, sexual harassment affects selection of medical specialty and residency programs (US, Japan, Sweden: Best et al. 2010; Stratton et al. 2005; George 2007; Nagata-Kobayashi et al. 2006; Larsson et al. 2003).

Occupational gender segregation

Occupational gender segregation may be observed where male and female students choose different courses of study. In the US, it was found that women are more likely to choose programs with higher proportions of women. (Jagsi et al. 2013). Physical violence against health workers—and female health workers and nurses in particular—is an “endemic problem” in health care systems across the world (Gillespie et al. 2013, Gerberich et al. 2005).

Suggested data analyses

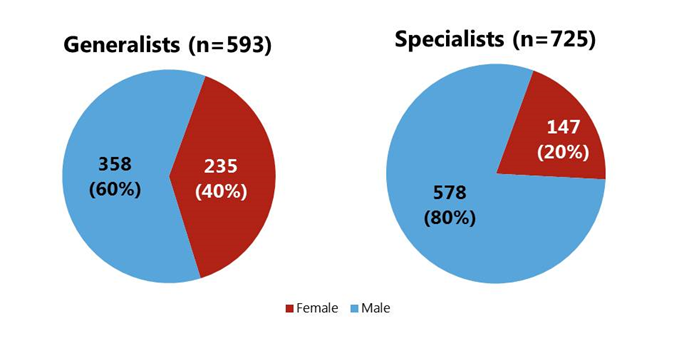

Gender distribution of medical specialists vs. generalists: Consider the case of generalist vs. specialist doctors in Kenya: four in ten generalists are female, but only two in ten specialists are female. This sex-disaggregated analysis indicates that there are differences in the proportion of women vs. men who succeed in specializing, which requires additional training.

Doctors by Specialty and Sex, Kenya 2010

Source: Newman et al. 2011

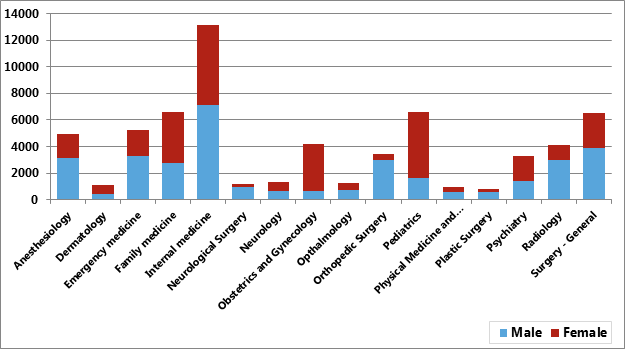

The gender representation of specialists may also vary by specialty. Using the Association of American Medical Colleges 2015 Report of Residents, a sex-disaggregated analysis of the number of active U.S. and Canadian medical school graduates reveals that 47.1% of all residents were women. However, women make up a larger proportion of residents in family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry, while men make up a larger proportion of residents in anesthesiology, emergency medicine, internal medicine, radiology, and surgery (AAMC 2015).

Number of Active Medical Residents by Specialty and Sex in the United States and Canada, 2013-2014

Source: AAMC 2015

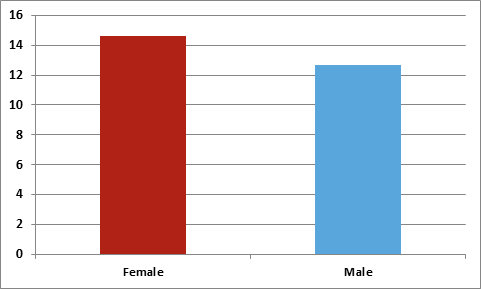

Average Years to Promotion for Nurse-Midwives in Kenya, 2011 (N=17,526)

Source: Newman et al. 2011

Qualitative research, surveys, focus group discussions, or other special studies with health professional students and health workers can help you to understand the underlying factors and dynamics contributing to challenges at admission and entry, and whether gender stereotypes or caregiver responsibilities discrimination prevent male and/or female students from successfully entering programs of study.

Ask Yourself:

|